Recently, Professor Anne-Marie Reynolds at Juilliard asked me to do a research assignment: to spend time in the library cataloguing memoirs of composers from after 1850. I couldn't find a satisfactory and comprehensive list of composer memoirs on the internet, so I thought this list might be of help to others. It is by no means comprehensive, but it does contain the autobiographies, memoirs, letters and essays I found in the stacks of Juilliard's Lila Acheson Wallace Library. I've included the Library of Congress call numbers at the end of each citation.

Please leave a comment if you have suggestions to add to this list!

Adams, John. Hallelujah Junction: Composing an American Life. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008. ML225 Ad18 A3h

Adams, John Luther. Winter Music: Composing the North. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2004. ML225 Ad185 A7w

Amram, David. Vibrations: The Adventures and Musical Times of David Amram. New York: The Viking Press, 1968. ML225 Am76 A3v

Argento, Dominick. Catalogue Raisonné As Memoir: A Composer’s Life. Minneapolis:University of Minnesota Press, 2004. ML225 Ar37 A3c

Babbitt, Milton. The Collected Essays of Milton Babbitt. Edited by Stephen Peles. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003. ML225 B113 A7e

Banfield, William C. Representing Black Music Culture: Then, Now, and When Again? Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2011. ML225 B224 A3re

Bartók, Béla. Essays. Selected and edited by Benjamin Suchoff. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1976. ML225 B285 A7s

Basie, Count. Good Morning Blues: The Autobiography of Count Basie. Collected by Albert Murray. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 1985. ML225 B292 A3g

Beckwith, John. Unheard Of: Memoirs of a Canadian Composer. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2012. ML225 B389 A3un

Berlioz, Hector. The Memoirs of Hector Berlioz. Translated and edited by David Cairns. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002. ML225 B456 A3m 2002

Bernstein, Leonard. Findings. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1982. ML225 B458 A3f

Boulez, Pierre. Stocktakings From an Apprenticeship. Collected by Paule Thevenin. Translated by Stephen Walsh. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1991. ML225 B664 A7n

Bowles, Paul. Paul Bowles on Music. Edited by Timothy Mangan and Irene Herrmann. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2003. ML225 B682 A7p

Britten, Benjamin. Britten on Music. Edited by Paul Kildea. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2003. ML225 B778 A7k

Busoni, Ferruccio. The Essence of Music and Other Papers. Translated by Rosamond Ley. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1957. ML225 B966 A7l

Cage, John. Silence: Lectures and Writings. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1967. ML225 C117 A7s

Carter, Elliott. The Writings of Elliott Carter: An American Composer Looks at Modern Music. Compiled, edited, and annotated by Else Stone and Kurt Stone. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1977. ML225 C245 A7w

Casella, Alfredo. Music in My Time: The Memoirs of Alfredo Casella. Translated and edited by Spencer Norton. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1955. ML225 C267 A3m

Colgrass, Michael. Adventures of an American Composer. Edited by Neal and Ulla Colgrass. Galesville, MD: Meredith Music Publications, 2010. ML225 C681 A3a

Copland, Aaron, and Vivian Perlis. Copland: 1900 Through 1942. New York: St. Martin’s/Marek, 1984. ML225 C792 A3c

Cowell, Henry. Essential Cowell: Selected Writings on Music. Edited by Dick Higgins. Kingston, NY: McPherson & Company, 2001. ML225 C839 A7e

Debussy, Claude. Debussy on Music: The Critical Writings of the Great French Composer Claude Debussy. Collected by François Lesure. Translated and Edited by Richard Langham Smith. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1977. ML225 D354 A7d

Dohnányi, Ernst von. Message to Posterity. Translated by Ilona von Dohnányi. Edited by Mary F. Parmenter. Jacsonville, FL: The H. & W. B. Drew Company, 1960. ML225 D682 A3

Dyson, George. Dyson’s Delight: An Anthology of Sir George Dyson’s Writings and Talks on Music. Edited by Christopher Palmer. London: Thames Publishing, 1989. ML225 D995 A7p

Eisler, Hanns. A Rebel in Music: Selected Writings. Edited by Manfred Grabs. Translated by Marjorie Meyer. London: Kahn & Averill, 1999. ML225 Ei87 A7p

Elgar, Edward. Letters to Nimrod: Edward Elgar to August Jaeger, 1897-1908. Edited and annotated by Percy M. Young. London: Dennis Dobson, 1965. ML225 El32 A5y

Engel, Lehman. This Bright Day: An Autobiography. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co, Inc., 1974. ML225 En32 A3t

Falla, Manuel de. On Music and Musicians. Translated by David Urman and J.M. Thomson. London: Marion Boyars, 1979. ML225 F191 A7o

Fox, Charles. Killing Me Softly: My Life in Music. Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2010. ML225 F83 A3k

Glass, Philip. Words Without Music: A Memoir. New York: Liveright Publishing Company, 2015. ML225 G463 A3wo

Gounod, Charles. Autobiographical Reminiscences with Family Letters and Notes on Music. Translated by W. Hely Hutchinson. London: William Heinemann, 1896. ML225 G741

Henze, Hans Werner. Bohemian Fifths: An Autobiography. Translated by Stewart Spencer. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999. ML225 H399 A3b

Hindemith, Paul. A Composer’s World: Horizons and Limitations. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1969. ML225 H585 A7c 1969

Honneger, Arthur. I Am a Composer. Translated by Wilson O. Clough. London: Faber and Faber Ltd, 1951. ML225 H756 A3i

Ives, Charles. Memos. Edited by John Kirkpatrick. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1972. ML225 Iv3 A3m

Janáček, Leoš. Janáček’s Uncollected Essays on Music. Edited and translated by Mirka Zemanová. London: Marion Boyars, 1989. ML225 J251 A7z

King, B.B. Blues All Around Me: The Autobiography of B.B. King. New York: Icon !t Itbooks, 1966. ML225 K58 A3bl

Krenek, Ernst. Horizons Circled: Reflections on My Music. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1974. ML225 K882 A3h

Mason, Lowell. A Yankee Musician in Europe: The 1837 Journals of Lowell Mason. Edited by Michael Broyles. Rochester, NY: The University of Rochester Press, 1990. ML225 M3814 A3b

Mason, William. Memories of a Musical Life. New York: The Century Co., 1902. ML225 M3818 A3m

Massenet, Jules Emile Frederic. My Recollections. Translated by H. Villiers Barnett. Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1970. ML225 M384 A3

Milhaud, Darius. Notes Without Music. Translated by Donald Evans. Edited by Rollo H. Myers. London: Denis Dobson Ltd, 1952. ML225 M599 A3n 1952

Nielsen, Carl. Living Music. Translated by Reginald Spink. Copenhagen: Wilhelm Hansen Music Forlag, 1968. ML225 N554 A7l

Offenbach, Jacques. Orpheus in America: Offenbach’s Diary of His Journey to the New World. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1957. ML225 Of2 1957

Partch, Harry. Bitter Music: Collected Journals, Essays, Introductions, and Librettos. Edited by Thomas McGeary. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1991. ML225 P257 A7m

Penderecki, Krzysztof. Labyrinth of Time: Five Addresses for the End of the Millennium. Chapel Hill, NC: Hinshaw Music, 1998. ML225 P373 A7l

Poulenc, Francis. Diary of My Songs. Translated by Winifred Radford. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1985. ML225 P864 A3r

Prokofiev, Sergei. Soviet Diary 1927 and Other Writings. Translated and edited by Oleg Prokofiev. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1991. ML225 P944 A3p

Reger, Max. Selected Writings of Max Reger. Edited and translated by Christopher Anderson. New York: Routledge, 2006. ML225 R263 A7s

Reich, Steve. Writings About Music. Halifax: The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1974. ML225 R271 A7w

Rimsky-Korsakoff, Nicolay Andreyevich. My Musical Life. Translated by Juday A. Joffe. Edited by Carl Van Vechten. New York: Tudor Publishing Co., 1936. ML225 R469 A3m

Rorem, Ned. Setting the Tone: Essays and a Diary. New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1983. ML225 R692 A38

Rubinsein, Anton. Autobiography of Anton Rubinstein: 1829-1889. Translated by Aline Delano. New York: Haskell House Publishers, Ltd., 1969. ML225 R825 A3

Saint-Saëns, Camille. Musical Memories. Translated by Edwin Gile Rich. Boston: Small, Maynard & Company, 1919. ML225 Sa28 A7m

Satie, Erik. A Mammal’s Notebook. Edited by Ornella Volta. Translated by Anthony Melville. London: Atlas Press, 2014. ML225 Sa83 A7m

Schoenberg, Arnold. Style and Idea. Edited by Leonard Stein. Translated by Leo Black. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1975. ML225 Sch63 A7s

Scott, Cyril. Bone of Contention: Life Story and Confessions. New York: Arco Publishing Company, Inc., 1969. ML225 Sco83 A3

Seeger, Pete. Where Have All the Flowers Gone: A Singalong Memoir. Edited by Michael Miller and Sarah A. Elisabeth. New York: A SingOut! Publication, 2009. ML 225 Se317 A32w

Segovia, Andrés. An Autobiography of the Years 1893-1920. Translated by W.F. O’Brien. New York: Macmillian Publishing Co., Inc., 1976. ML225 Se375 A3

Sessions, Roger. The Musical Experience of Composer, Performer, Listener. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1950. ML225 Se72 A7m

Shankar, Ravi. Raga Mala: The Autobiography of Ravi Shankar. Edited by George Harrison. New York: Welcome Rain Publishers, 1997. ML225 Sh18 A3r

Shaw, Artie. The Trouble with Cinderella: An Outline of Identity. New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1979. ML225 Sh26 A3t

Shschedrin, Rodion. Autobiographical Memories. Translated by Anthony Phillips. Mainz: Schott, 2012. ML225 Sh29 A3av

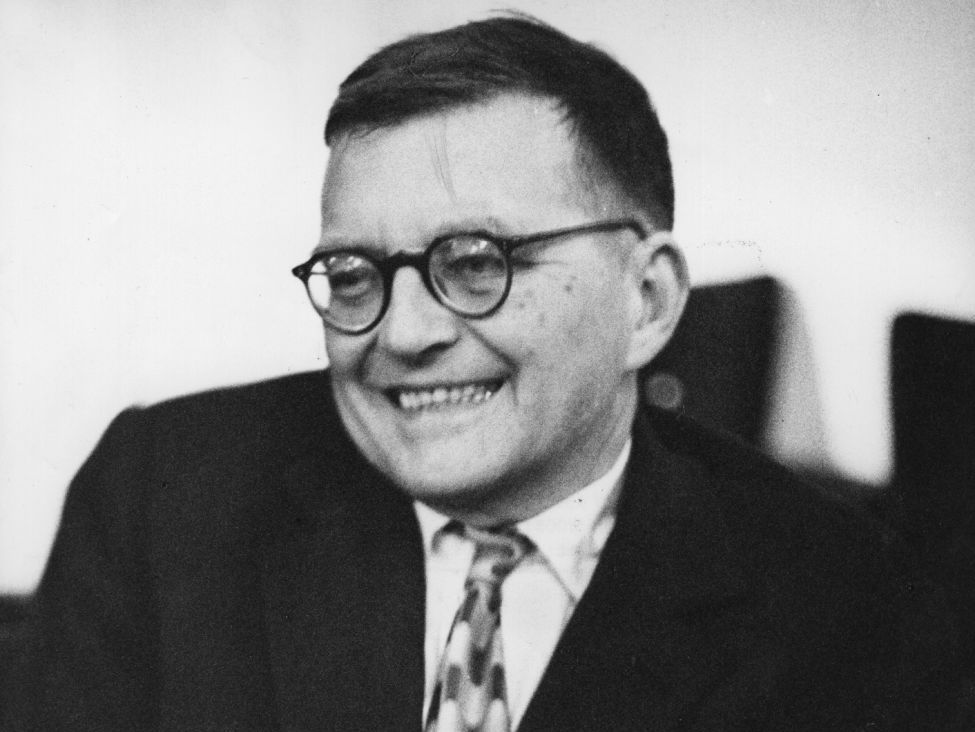

Shostakovich, Dmitri. Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich. Edited by Solomon Volkov. Translated by Antonina W. Bouis. New York: Limelight Editions, 2004. ML225 Sh82 A3 2004

Sondheim, Stephen. Reading Stephen Sondheim: A Collection of Critical Essays. Edited by Sandor Goodhart. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc. 2000. ML225 So57 R227g

Still, William Grant. The William Grant Still Reader: Essays on American Music. Edited by Jon Michael Spencer. Durham: Duke University Press, 1992. ML225 St54 A7s

Stockhausen, Karlheinz. Stockhausen on Music. Compiled by Robin Maconie. London: Marion Boyars, 1991. ML225 St62 A7s

Stokowski, Leopold. Music for All of Us. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1943. ML225 St67 A7m

Strauss, Richard. Recollections and Reflections. Edited by Willi Schuh. Translated by L.J. Lawrence. London: Boosey & Hawkes Limited. ML225 St828 A3r

Stravinsky, Igor. An Autobiography. London: Calder & Boyars, 1975. ML225 St83 A3c 1975.

Stravinsky, Igor. Themes and Conclusions. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1982. ML225 St83 A3th 1982

Szymanowski, Karol. Szymanowski on Music. Translated and edited by Alistair Wightman. Musicians on Music, no. 6. London: Toccata Press, 1999. ML225 Sz93 A7s

Takemitsu, Toru. Confronting Silence: Selected Writings. Translated and edited by Yoshiko Kakudo and Glenn Glasow. Berkeley, CA: Fallen Leaf Press, 1995. ML225 T139 A7c 1993

Tavener, John. The Music of Silence: A Composer’s Testament. Edited by Brian Keeble. London: Faber and Faber, 1999. ML225 T198 A3m

Tchaikovsky, Piotr Ilyich. Letters to his Family: An Autobiography. Translated by Galina von Meck. Annotated by Percy M. Young. New York: Stein and Day Publishers, 1981. ML225 T22 A5y

Thomson, Virgil. Virgil Thomson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1966. ML225 T387 A3v

Tippett, Michael. Tippett on Music. Edited by Meirion Bowen. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1995. ML225 T499 A7bo

Vaughan Williams, Ralph. Vaughan Williams on Music. Edited by David Manning. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2008. ML225 V466 A7m

Verdi, Giuseppe. Letters of Giuseppe Verdi. Selected, translated, and edited by Charles Osborne. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971. ML225 V548 A5o

Verdi, Giuseppe, and Arrigo Boito. The Verdi-Boito Correspondence. Edited by Marcello Conati and Mario Medici. Translated by William Weaver. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1994. ML225 V584 C243c 1994

Wagner, Richard. My Life. Translated by Andrew Gray. New York: Da Capo Press, 1992. ML225 W125 A3m 1992

Walker, George. Reminiscences of an American Composer and Pianist. Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2009. ML225 W152 A3r

Walter, Bruno. Theme and Variations: An Autobiography. Translated by James A. Galston. New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1946. ML225 W172 A3t

Willson, Meredith. And There I Stood With My Piccolo. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009. ML225 W686 A3a 2009

Wolf, Hugo. Letters to Melanie Köchert. Edited by Franz Grasberger. Translation by Louise McClelland Urban. New York: Schirmer Books, 1991. ML225 W831 A5k 199